Teabowl as tactile & functional object: considering Bonnie Kemske’s definition

Once I had decided to focus on the teabowl as a form, I began looking for sources which set out a discussion of them from first principles, particularly with reference to the context of the tea ceremony — my interest in which first motivated me to work with clay. Happily, I quickly discovered Bonnie Kemske’s The Teabowl: East and West (Herbert Press, 2017). A beautiful object in its own right, at once comprehensive and deeply personal in its approach, it is very likely to be a touchstone for me going forward. Kemske’s discussion of her own experience, finding her early study in the arts and various other disciplines unrewarding and hollow until she discovered chado, which thereafter was an animating focus for her, resonates deeply with me, as details aside it is very similar to my own experience.

While as her chosen title suggests, Kemske’s approach to the teabowl as a form involves discussion of a wide range of different interpretations of the teabowl as a form, her discussion begins by discussing the teabowl within the context of Tea — as she notes, the philosophy of Tea is part and parcel of how the form has been created, appreciated, and experienced within Japan. It is worth quoting in full (below) -

A list of teabowl attributes derived from the tea ceremony

A chawan , or teabowl, is a handleless bowl. The dimensions vary, but are most commonly about twelve or thirteen centimetres across and nine or ten centimetres in height.

It should be shaped so the fingers can lift it from underneath, and be shallow enough that the thumb reaches the rim. This may mean the inclusion of a foot ring.

It should stand securely on tatami without wobbling.

It should be heavy enough to feel substantial, but light enough to not be cumbersome, usually about 300-500 grams, depending on the type of teabowl.

The teabowl should fit snugly and pleasurably in the hands, with the left hand holding it underneath and the right hand wrapped around the side.

The rim should feel pleasing and engaging to the lips.

The clay should and firing qualities should be such that the bamboo implements tapped on its rim produce a mellow and satisfying sound.

The inside and outside of the teabowl should be smooth enough for a damp linen cloth to be run over the surfaces.

The inside bottom should be smooth enough that it does not damage the fine bamboo tines of the whisk. The bottom can be subtly shaped to create a reservoir for any tea and froth remaining after the guest has drunk.

The potter’s mark can be inside the foot ring or on the inside of the bowl, often on the left, but ultimately it is up to the host to determine the front of the teabowl.

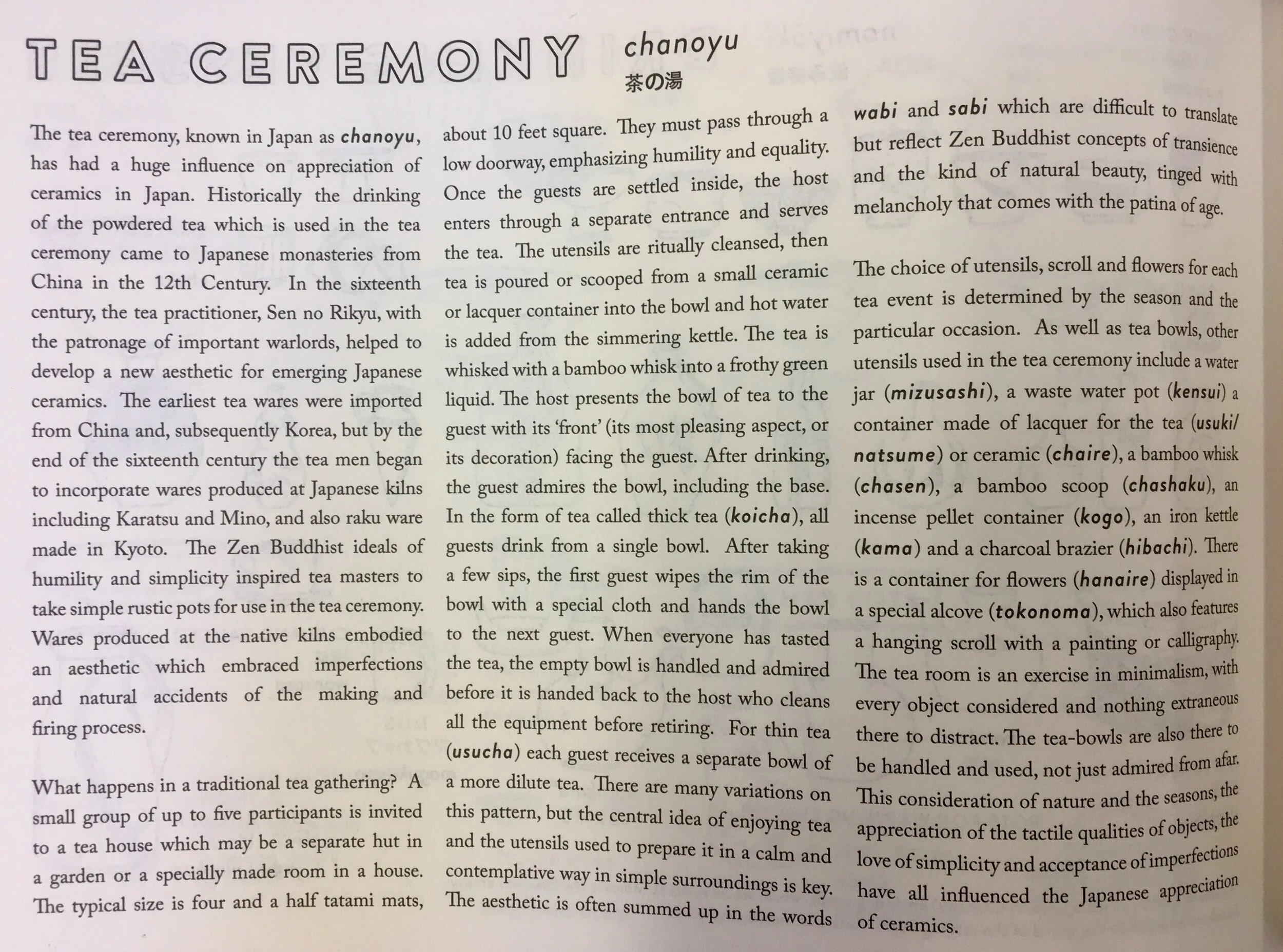

Discussion of the teabowl & tea ceremony in The Japanese Pottery Handbook

One of my favourite reference books both for making and for drawing & note-taking style is The Japanese Pottery Handbook. Their section on teabowls & the tea ceremony is concise but accurate in its outlining of the appeal of tea.